As providers of mental and behavioral health we enter the field with the desire to serve, to give back, and foster wellness in our communities. The stark reality is that we often struggle to meet the needs of our clients due to a lack of adequate community resources. Coming from working several years in the delivery of crisis services for adults, that struggle is very real to me. It is even more real for providers who specialize in the mental and behavioral health needs of children and adolescents.

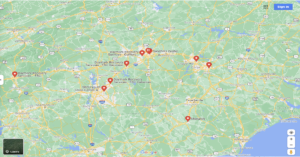

There’s a teenager in crisis in need of services or referral. Where do you refer them? How do you as a provider insure their safety, and get them the best possible care? Do a Google search for my state of North Carolina and nine 24-hour crisis centers show up on the map. Only two specialize in child/adolescent care (and neither has a behavioral health urgent care attached to the services they provide); six programs in south central and western NC will assess youth, but they cannot provide extended observations due to the fact they are designated adult facilities.

There’s a teenager in crisis in need of services or referral. Where do you refer them? How do you as a provider insure their safety, and get them the best possible care? Do a Google search for my state of North Carolina and nine 24-hour crisis centers show up on the map. Only two specialize in child/adolescent care (and neither has a behavioral health urgent care attached to the services they provide); six programs in south central and western NC will assess youth, but they cannot provide extended observations due to the fact they are designated adult facilities.

What’s next? Call the local hospital or managed care organization based on the type of insurance your client has, and send the youth to their emergency department (ED).

As a trained mental health provider, my next thought is, “Would you take your computer to an auto mechanic for repairs?” That would be impractical and not produce the needed results. Hospital EDs are equipped to aid the sick and injured. They are frequently very frenetic environments, and there is no time to stop and devote the needed time to a child/teen in crisis. Even if they had time, ED staff are not adequately trained to provide the needed support behavioral health issues demand. Members of the community in mental/behavioral health crisis are frequently (and sometimes routinely) warehoused in emergency rooms while waiting to be placed in a state mental health hospital. There is little to no intervention provided outside of a brief crisis assessment and medication to calm anxiety or dangerous behaviors.

As I noted, hospital staff have their hands more than full with the amount of medical issues their patients present in the ED. One way the medical system is addressing that problem is through the establishment of “Urgent Care” centers — programs in the community that can divert cases from overcrowded EDs while continuing to provide individuals the appropriate physical healthcare they need. It’s time we consider that model for mental and behavioral health issues as well – and look at creating a new kind of Behavioral Health Urgent Care (BHUC).

Opening in early 2022, The Hope Center for Youth and Family Crisis in Fuquay-Varina, North Carolina will be a partnership between KidsPeace and Alliance Health. The Hope Center is a 24-hour, seven days a week, 365 days a year program designed to provide crisis assessments, observation and short-term support to youth in an environment that specializes in their mental and emotional wellness and care.

Under the BHUC model, a teen in crisis can be referred to The Hope Center where they and their family can meet and work with a team of admission specialists, parent partners, qualified professionals, licensed clinicians, nurses, mental health technicians and providers who are all caring and trained to support the needs of the teen and his/her family at a difficult time. The focus is on providing a therapeutic, least restrictive, comforting experience.

How does it work? Let’s look at an example of a youth in crisis, whom we call Joe.

Joe’s story

When Joe and his family arrive at The Hope Center, the first thing they notice is, “This really doesn’t look like a hospital.” There are murals on the walls in the lobby and the waiting area is painted in bright happy and calming colors. An admission specialist greets Joe and his family with a smile, asks them for some important information to get the process started, and asks Joe and his family, “Is there anything I can do to make you more comfortable?” Joe is a little nervous and asks for a drink. He is given a small glass of tea or juice, and he and his family take a seat. (Had he been a small child he may have been offered a stuffed animal for comfort)

Joe’s mom and dad appear anxious, and the admissions specialist decides the best next step is for the “family partner” to greet them. The Hope Center’s family partner is a person who has lived experience in caring for a loved one with mental/behavioral health challenges, and supports the youth and family throughout their time at the center. The family partner greets Joe and his family and answers their questions – providing another layer of comfort in the process.

Within 15 minutes of walking through the door at The Hope Center, Joe and his family are sitting down with our licensed clinician and talking about what brought them to seek assistance. After the brief crisis assessment, Joe meets with the nurse and has a short physical health assessment while his parents talk further with the clinician or qualified professional about what the next steps should be.

From triage to disposition the entire intake for Joe lasts approximately one hour. Had he been sent to the local ED, he may still be in the waiting room at this point. Had he been sent to another behavioral health urgent care that does not specialize in youth or provide 23-hour observation, he may have been sent to the ED anyway — to begin that wait all over again.

After assessment, and based upon the needs of Joe and his family, it is decided that Joe will remain at the center overnight for observation. He spends the rest of the day being supported and observed for safety while engaging with center staff and other youth in therapeutic socialization and treatment activities. He is provided with necessary medication per provider orders and the consent of his guardian, a quiet place to rest in comfortable recliners, and is continually assessed for the next 23 hours.

The next day, if it’s determined that Joe can return safely home, the family partner and treatment team will work together with his family to arrange for continued treatment and support. The family partner will assist in communicating with other providers, check in on Joe and his family, and even accompany them to his first appointment if needed. Joe’s case, again, is like that of someone with a physical illness or injury who can be treated appropriately at an urgent care facility without burdening the resources of the local ED.

Linking BHUC with inpatient crisis intervention

If, on the other hand, it’s determined Joe needs more intensive treatment, the BHUC staff will refer his case to an inpatient crisis center. Initially The Hope Center will rely on local mental/behavioral health hospitals to support inpatient admissions for youth with the need for longer-term care. But within a few months of opening, it will complete the licensure process for a 16-bed inpatient Facility Based Crisis unit, where youth like Joe can transition to a higher level of onsite treatment lasting up to two weeks.

While in The Hope Center’s Facility Based Crisis unit Joe will have around-the-clock monitoring for safety, support from qualified professionals, skilled nursing, psychiatric evaluation and follow up, regular treatment team and case manager support, and encouragement to engage in social and physical activities with peers.

The Hope Center will be the first program in North Carolina to bring together behavioral health urgent care and facility based crisis services for children and youth in a single facility. The ability to quickly assess, begin providing support, and transition through the system of care all in one location will increase safety, improve outcomes, and reduce costs for consumers and stakeholders alike.